From Pritt stick in school bags to Audi sports cars, adhesives have come a long way since natural gums and resins, and new high-tech variations are currently top of the list for carmakers as they seek ways to make cars lighter and tougher.

For auto suppliers like Henkel, PPG and Atlas Copco, providing tailor-made adhesives that can absorb the shock of a crash and reduce rattles allows them to push for higher prices – and make more profits.

Stricter emissions rules in major markets mean cars have to become more fuel-efficient and less polluting, which in most cases means they will have to be lighter than last year’s average weight of 1,400 kg.

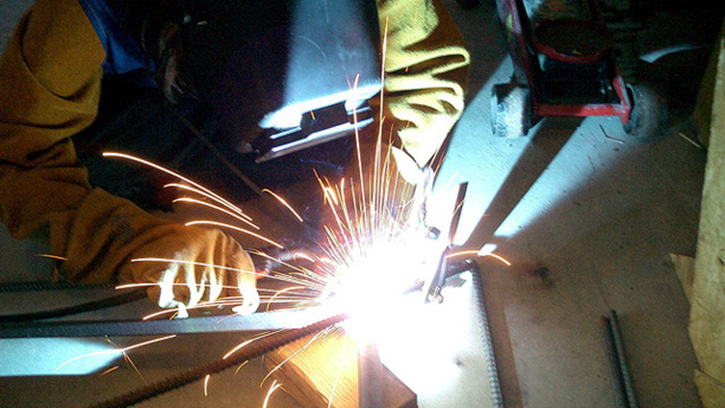

Companies like VW, Daimler, and PSA Peugeot Citroen are therefore using more aluminium and exotic composites, which cannot be welded together but have to be glued with adhesives that will not lose their strength and can hold together parts even at top speeds and high pressure.

That puts industrial adhesives – made up of chemicals like the polyolefins that are used in Croc shoes and tennis racket strings – at the top of carmakers’ shopping lists.

“Those who can demonstrate that their glue has something different to offer, and that it can be easily integrated into production processes, will achieve good margins,” said Fabrice Roghe, a partner specialising in industrial goods at Boston Consulting Group in Dusseldorf.

Henkel, the world’s largest maker of adhesives, is selling off divisions that deal with simpler industrial glues to focus on more complex and specialist products used on cars, airplanes or mobile phones.

The margin for its adhesive technologies division stood at 16.5 percent in the first quarter, outperforming the group as a whole, which had a margin of 14.9 percent.

New ideas

Although European car sales are this year headed for a sixth straight annual decline as government austerity and persistent unemployment hurt demand, global auto sales may surge 28 percent to 102 million cars by 2018, fuelled by growth in Asia and North America, according to research firm IHS Automotive.

The $2.6 billion to $3.9 billion market for automotive adhesives currently accounts for less than 10 percent of the global adhesives market, but industry experts forecast the amount of glue used in an average car may grow by at least a third over the next 5-10 years, from around 15 kg now.

As well as sealants that fill in tiny gaps in the various joints of a car, stronger structural adhesives can now be used to hold together and stiffen load-bearing parts and components like doors, bumpers and struts.

Audi’s $147,700 top-of-the-line R8, for example, is in large part fastened by advanced structural adhesives which have also been developed to withstand racetrack vibrations and fierce heat.

“We don’t buy glues off the peg but work very closely together with manufacturers on complex specific adhesive applications,” said Michael Zuern, head of materials engineering at Mercedes-Benz at Mercedes-Benz.

Sweden’s Atlas Copco entered the auto adhesives segment in 2011 through the acquisition of German company SCA-Schucker.

“It’s one of the product areas with the strongest growth since it’s driven by new techniques all the time, and the car makers’ new ideas,” said Mats Rahmstrom, head of the group’s business area Industrial Technique.

Losing weight

“Adding power makes you faster on the straights, subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere,” Colin Chapman, founder of Lotus cars, used to say.

But whereas it was once the preserve of race cars, lightweight is becoming more mainstream. Producers like Alcoa expect to more than triple sales of aluminium sheet to carmakers by 2015 as they opt for that over steel for doors, bumpers and cylinder heads.

Bernd Mlekusch, head of technology development at Audi, said the proliferation of lightweight composites may cause the amount of glue used in an Audi vehicle, which is often illustrated by carmakers in the total length of bonding substance used rather than weight, to swell to a length of 150 metres in coming years from 100 metres currently.

Because adhesive bonding increases the stiffness of the body shell, the vehicle can better absorb bumps and in-car noise is dampened, Mercedes’ Zuern told Reuters. It also makes for better handling and helps absorb the impact of a crash.

GM’s new CTS sedan uses 118 metres of structural adhesives, more than the length of a soccer field, helping to make the vehicle 40 percent stiffer than its predecessor.

Using aluminium for the doors of the CTS shaves 25 kg off the weight of the car, GM said.

Andrew Christie, a product manager at PPG’s engineered material solutions division in Germany, said there were fracture-toughened adhesives on the market which could absorb the energy of an impact far more efficiently than standard adhesives or even spot welds.

“One of the key things to surviving a crash is that the structure should absorb the impact and not you or I,” he said.

Still, adhesives aren’t without flaws.

In 2010, Fiat’s Ferrari brand recalled 1,248 458 Italia supercar models after determining that a special adhesive used to attach a heat shield inside the wheel-arch was prone to melting and had caused several cars to burst into flames.

Ferrari subsequently replaced the glued sections of the heat-shield with metal rivets.

Carmakers and adhesive suppliers work with research institutes like Fraunhofer in Germany to see how they can cure glues at lower temperatures and make sure they can be dispensed accurately by robots.

“Initially, automakers didn’t have the courage to admit that certain parts and sectors of the car require bonding. That’s well and truly over now,” said Manfred Peschka, an expert on adhesives at Fraunhofer’s facility in Bremen.